Two Shores

Appropriation, Counter-appropriation and Architecture of Transnational Exchange

Thesis Research by Jason Wu

Architecture 3020: Thesis Research Studio

House for Piranesi: Allegory Narratives, Drawing as Thesis, Triumph of the Fragment

Thesis Advisor: John Shnier

Fall 2022

Daniels Faculty

University of Toronto

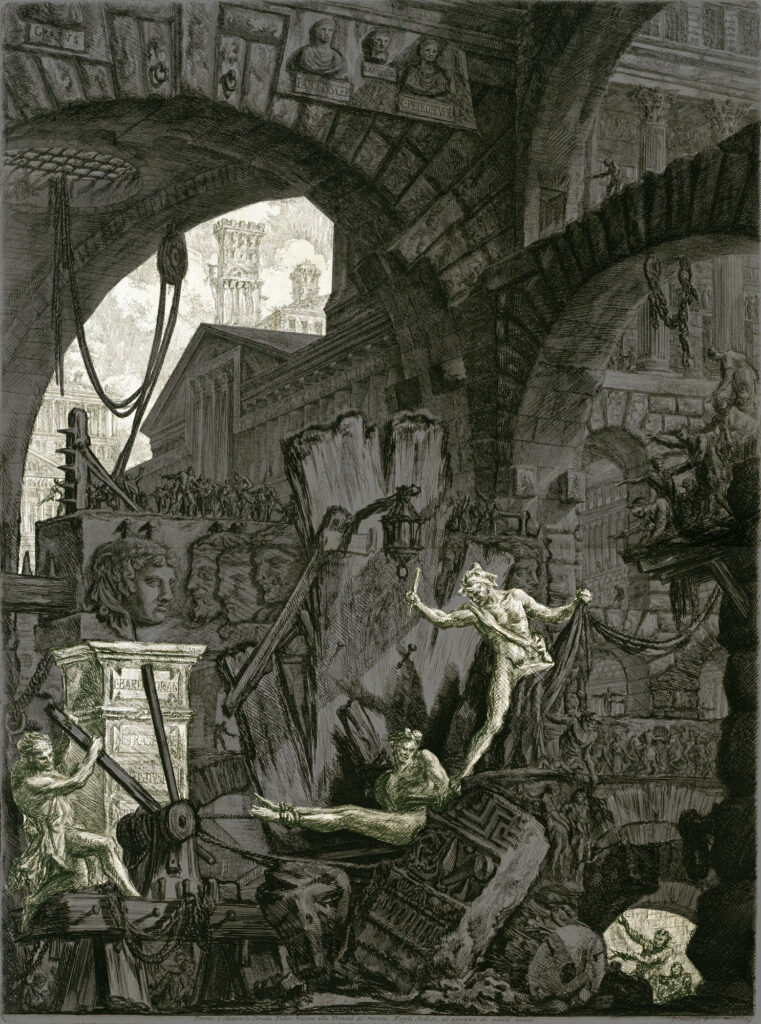

Key elements highlighted within The Man on the Rack. Image source: Giovanni Battista Piranesi, The Man on the Rack, etching with engraving, early 1770’s, (Royal Academy), https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/the-man-on-the-rack.

The departure point for this thesis drawing was the Italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s carcere etching The Man on the Rack, which sparked my intrigue because of several elements found in the imagined realm; figures engaged in torture, indistinguishable shadows looking for ways out, and the funerary boxes of those already lost to this carcere. Most importantly, however, there is an opening to the sky above, and architecture, seemingly Catholic campanile within a time of Roman antiquity, towering towards it. There is suffering in the foreground we stand upon, but a sublimity beyond the horizon.

These elements parallel the discourse within my thesis topic, which stems from indentured Chinese labourers who were exploited for their cheap labour as America and Canada engaged in a railway race beyond their western frontiers. It was absolutely vital for them to import a diligent and hardworking crowd on the other side of the continent to meet the expansion in the middle. As such, in Canada, the Chinese were only paid a fraction of the salaries of their white counterparts, while enduring some of the most relentless terrains.

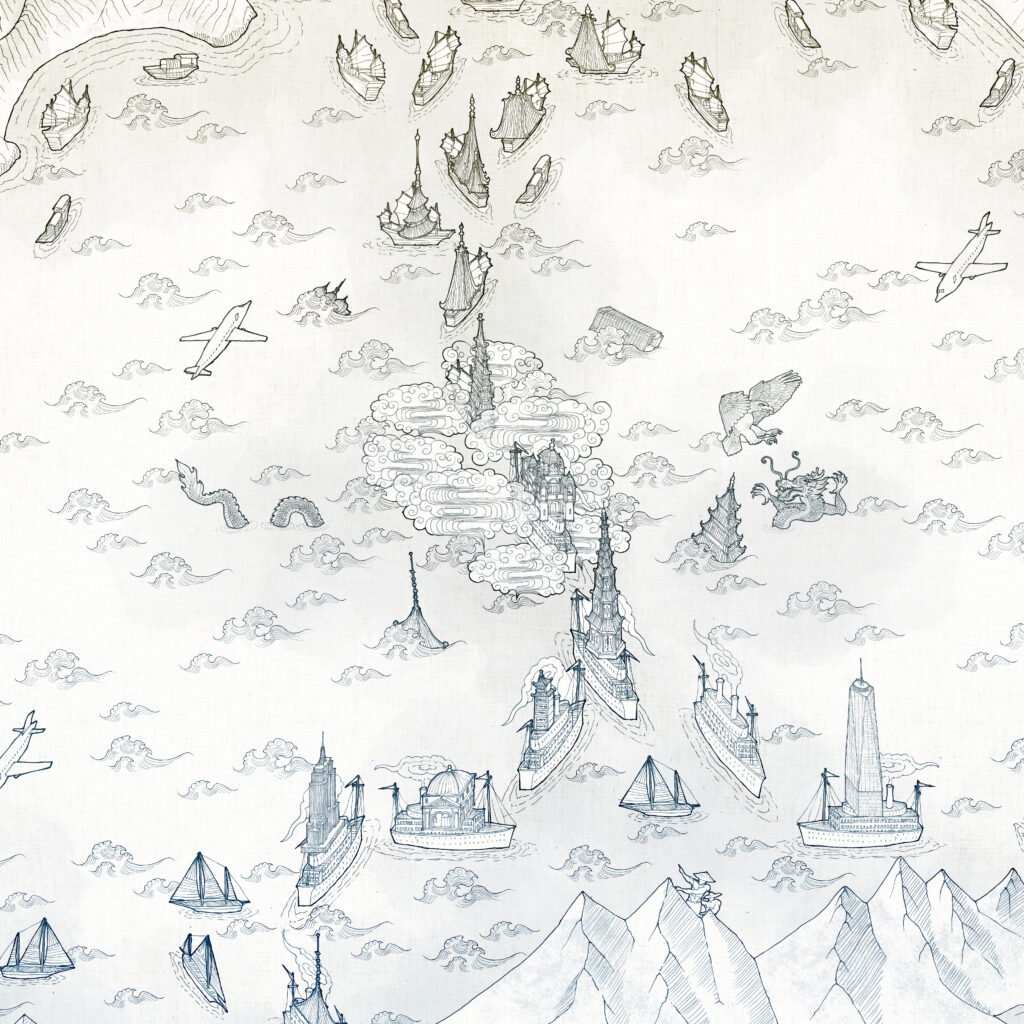

The ocean is a place of parallax; “on this shore is suffering, on the other is architecture reaching for the sky;” the same statement could be said from either shore. However, it is also the stage for combustion, where the collision of cultures and the clash of civilizations occur. The labourers who first came to North America were overwhelmingly from one region of Southern China, a county named Toishan. Through their unwelcomed stays on this continent, they accrued not only remittable wealth, but the taste for neo-classical architecture to build with that wealth.

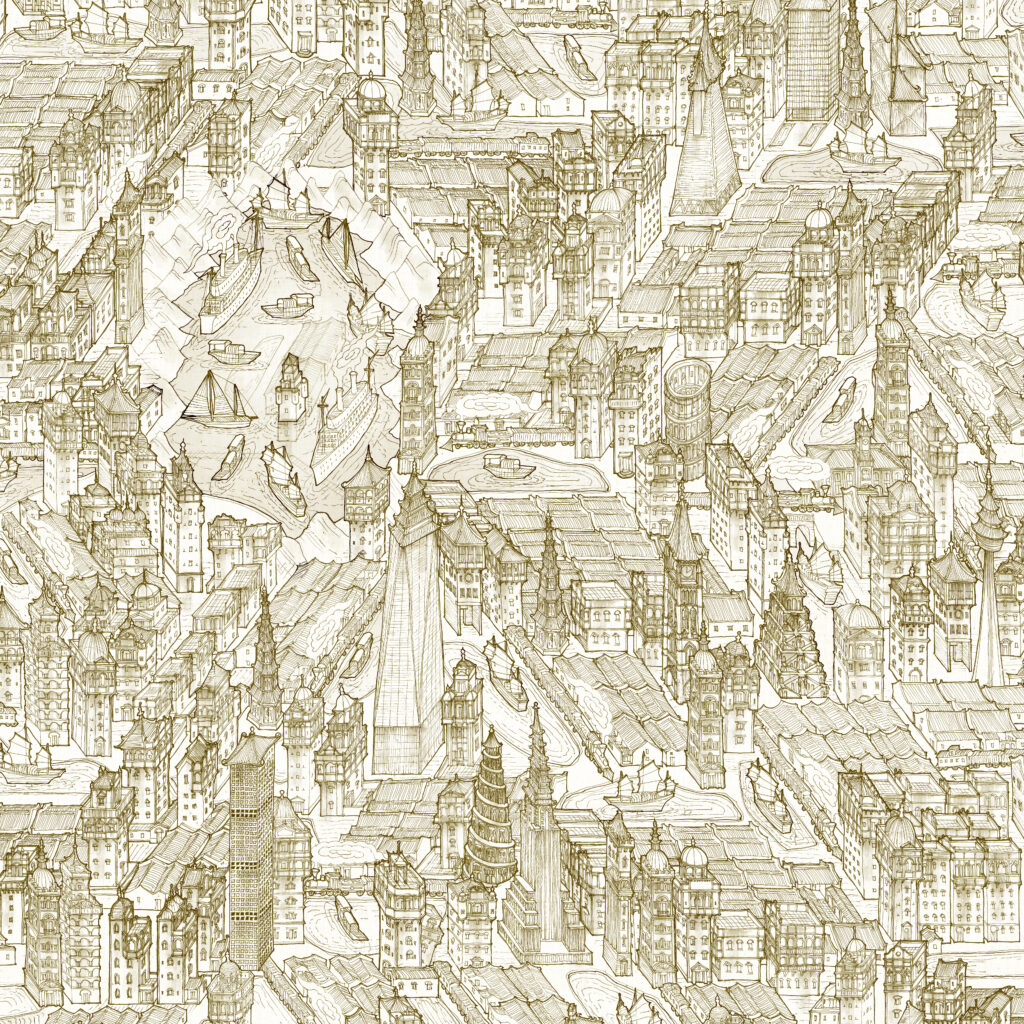

And so, the labourers’ rural county saw a construction boom – architecture towering to new heights, a typology called diaolou, made possible with reinforced concrete – created for housing and for protection due to their abnormality of size, shape and ornamentation. In this culture, leisure is not possible without work, and these villas weep with the embedded suffering of their creators.

In the West, Orientalism was a romanticized style rooted in colonialism, while across the pond, Neo-classicism was transfigured to fit the needs and wants of the Toishanese rural-sophisticated. In this drawing, appropriation is used to strip architecture void of their original iconography, layering in the content and context of another culture, and reiterating a culturally-enriched visual experience. Ancient and modern wonders of the West are diaolou-ified and pagoda-fied to suppress their significances.

This is the revenge of the exploited,

it is counter-appropriation.